I am known as King of the Dharma Instruments. It is my destiny to lead, as everyone listens for my voice to know when to start and stop chanting, when to chant quickly or slowly, and when to change from one tone to another.

Get this book at Buddha's Light Publications.

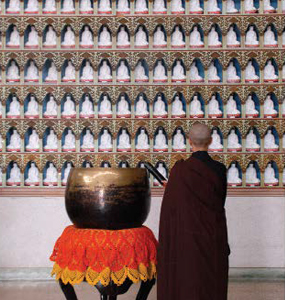

The great gong can be found in Buddhist temples usually to the right of the main altar. Ranging from thirty to sixty centimeters in diameter, great gongs are bowl-shaped and cast from copper. The gong is struck by the discipline master during Dharma services at the beginning to set the pace and the pitch of the chanting, and at the conclusion of the service to signal its end. The gong is also struck whenever senior monastics, great sages, or visiting abbots come to the temple and bow in the main shrine, one strike for each bow, as a respectful welcome.

Sometimes called a chime, the instrument comes in many shapes and sizes: large chimes, round chimes, tablet chimes, and handheld chimes. Tablet chimes, for example, are made of stone and shaped similar to the cloud board used to signal meals. The tablet chime is hung in the corridor leading to the abbot’s chambers, and it is sounded three times by the receptionist when a visitor is to see the abbot. The handheld chime, also called a hand bell, is shaped like a small bowl and is attached to a wooden handle by a knot through a hole in its center. The hand bell is struck with a small steel rod when bowing to the Buddha and chanting to indi-cate when to start or stop.

I do not recall in which year we great gongs first came to Bud- dhist temples in China. I think it might have been after Chan Master Mazu Daoyi had founded his monastery and Chan Master Baizhang Huaihai had established the monastic rules. I was then enlisted for my honorable duty.

I come from a long pedigree of the Brass family, but there are other distinguished alloys in my ancestry as well. I am known as King of the Dharma Instruments, but it is said that I am actually akin to the small hand chime, another one of the wondrous Dharma instruments in the monastery. It is my destiny to lead, as everyone listens for my voice to know when to start and stop chanting, when to chant quickly or slowly, and when to change from one tone to another. I live in the Great Hall of this temple. My place is right in front of all the other Dharma instruments. I feel most fortunate because my life is good and I have a fulfilling purpose.

Let me tell you about my contribution to my calling. When I sound one dong, the instruments follow my lead and start playing. When I sound two dongs, the instruments stop. I am like a bugle’s call in the military, telling the soldiers when to advance and when to retreat. I take great pride in my role. When I sound my voice, I must be right on cue. There is no room for dereliction of duty in my position. Just as if the bugle were to make a mistake, then the soldiers would become disorderly; it is the same in my case. If I were to err, then all the other instruments and the Buddhist prac-titioners would most certainly fall out of step. The chanters could not keep their cadence in unison. Everything would quickly fall into a terrible discordant cacophony. Therefore, you can see what an honorable and important office I discharge.

A great gong is different from the other Dharma instruments in another way. Any one of the monastics can strike them, but such is not the case with me. The monastic who strikes me has a special title: chant leader. The chant leader is an important administra-tor in the monastery who is not only required to be familiar with temple etiquette but must also possess a superior vocal quality for chanting. Just as in a traditional Chinese opera, the actor in the leading role has to direct the performance, so it is with the chant leader during a Dharma service. There is a very specific technique to use when striking a great gong, and the chant leader must not make a careless mistake. Next to the chant leader’s meditation cushion in the meditation hall is a small wooden plaque on which the following grave admonition is inscribed:

A practitioner’s life of wisdom relies on you fulfilling your office properly.

If you perform your duty carelessly, you shall bear that wrongdoing.

As you can see, striking the great gong is not a small, insig-nificant task.

The chant leader's position has always been an important and responsible one because of the great gong’s critical role in the Dharma service. Many envy that position, claiming that the chant leader simply likes to show off. Some monastics erroneously be-lieve that they would gain honor and importantance if they only had the opportunity to strike me. Thus, I have, at times, been the object of the struggle for power. I have often been exploited by the monastics who have selfish reasons for being appointed to strike me. These monastics will typically be the only ones competing for the position of chant leader, because, in general, the more mature cultivators have no interest in engaging in such petty rivalries.

I have already called your attention to the fact that I am the leader of the other Dharma instruments used for chanting. As a rule, people are not allowed to arbitrarily strike me. However, in the past, elderly, superstitious women would come to the temple and cry, “If I come to offer incense but don’t strike the great gong, then the bodhisattvas will not believe that I’m sincere.” Then with little regard, they would march right up and start pounding on me. Bang! Bang! Clang! Clang! The master in charge of the Great Hall would be at a loss for words. Personally, I entertained these mis-guided actions as only a mild disturbance, and I secretly laughed at the naiveté of the elderly women. I am sure that the bodhisattvas care more about the sincerity of one’s intentions when offering incense, rather than whether or not one has struck a great gong.

During times of peace in the land, my life has been very stable. But, unfortunately, during times of war, I have suffered greatly. There have been three disastrous times of persecution in the his-tory of Chinese Buddhism. We refer to these as the Four Scourges of Buddhism1. Emperor Zhou Shizong only saw me as an object of valuable metal, and he ordered that all brass bells like me be collected and stamped into imperial currency. When I heard about this plan, I was terrified! I believed my life was doomed! Fortu-nately for me, Emperor Zhou’s rule lasted only a few years before he was overthrown. My life was spared, and a safe existence was assured for me.

Many centuries passed in this way. Then the Luguo Bridge Incident2 happened. On July 7, 1937, my homeland was invaded by the Japanese army. The many monastics who did not wish to live under Japanese rule followed the Chinese government as it retreat-ed to the unoccupied areas. The monastics carried many valuable Buddhist treasures with them, but my great weight caused them to leave me behind. I remained in the occupied territory, and I was destined to bear another long period of hardship.

After eight years of occupation, the Japanese army was run-ning short of guns and ammunition. In their desperation, the sol-diers turned to me, thinking that my body could be smelted into guns and bullets. Hearing the soldiers telling the monastics about their plans was like a bolt of lightning striking me! I thought that my fate had been sealed, and that, this time, I was most certainly finished!

Fortunately, the monastics did not want me destroyed. They came up with a clever plan to hide me in the corner of one of the rooms in the temple. There I would be concealed from the view of the Japanese soldiers. A monastic told the soldiers that the monas-tery had been without a great gong for many years, and offered to show them around to see for themselves.

As luck would have it, the Japanese soldiers failed to find my hiding place, so they had to abandon their plans. I remained in my dark hiding place for eight years, patiently waiting to be res-cued—steadfastly waiting for victory and freedom. Finally, the war ended. There was peace. Once again, I proudly took my place at the center of the Great Hall.

After this ordeal, I made a bold statement: All who want to destroy me will end up only destroying themselves. I am a Dharma instrument, dedicated to only being used during Dharma services. The “eyes and ears” of heavenly beings can never be destroyed by mere mortals.

Unfortunately, disaster, like a bad penny, turned up again. A civil war broke out, and Buddhism was in great danger. After all that had happened throughout my long history, I decided that the place of my birth was no longer safe for me. I did not want to live another eight years shrouded in darkness, so I traveled by ship over the ocean to Taiwan. When I arrived, I wandered around like a vagabond. Once again, hard times had found me. I was certain that my days of glory were forever in the past!

In my initial days here in Taiwan, I was not treated with the dignity and respect that had finally been accorded me in my home-land. While in China—with the exception of those naïve old ladies who insisted on striking me when they offered incense—only the trained chant leader would strike me. But in Taiwan, anyone could hit me! Mr. Li struck me. Mr. Zhang beat me. Numerous monas-tics hit me. Laypeople pounded on me. Furthermore, the people here did not know the proper technique when striking me, so my rhythm was shamefully uneven and my tone terribly discordant. The inexperienced monastics occasionally made mistakes and dis-tracted the chant leader. When that happened, the two would ex-change uneasy glances. These distractions would make the chanters lose their concentration. Consequently, I could tell that their minds wandered off to other thoughts, detracting from their cultivation.

There was one other difference in the way I was treated. In China, the chanting always started with the chant leader striking me. In Taiwan, sometimes the chant leader would begin by striking me, but sometimes before he started to intone the chant, the pre-siding monastic would also jump in, throwing him off and causing discord. By the time the chant leader was back on track, many striking cues had already been missed. What can I say about this improper situation?

What distressed me even more was when the abbot would take me along for funeral services and other rituals. This was a very disheartening experience, because the chanting ceremonies in Taiwan included words, rites, and even memorial tablets of folk religions or other traditions, rather than following traditional Bud-dhist ritual.

I wondered about what would happen to me. Since I had been exposed in public as a party to these unorthodox practices, if I ever returned to my homeland, how could I face my fellow Dharma instruments? Thank goodness that some compassionate followers of the Buddha did not allow my life to continue to go down such a path. They came to my rescue and installed me in my current place of honor—the glorious Great Hall of this wonderful temple, where I am, once again, King of the Dharma Instruments.

What's New?

NOVEMBER

Humble Table, Wise Fare

INSPIRATION

Recorded by Leann Moore

A moment of loving-kindness:

all things are good;

a moment of anger:

a thousand situations turn evil.

Dharma Instruments

Venerable Master Hsing Yun grants voices to the objects of daily monastic life to tell their stories in this collection of first-person narratives.

Sutras Chanting

The Medicine Buddha SutraMedicine Buddha, the Buddha of healing in Chinese Buddhism, is believed to cure all suffering (both physical and mental) of sentient beings. The Medicine Buddha Sutra is commonly chanted and recited in Buddhist monasteries, and the Medicine Buddha’s twelve great vows are widely praised.

Newsletter

What is happening at Hsingyun.org this month? Send us your email, and we will make sure you never miss a thing!